Collagen For Pregnancy

Collagen protein from the very start.

While clearly beneficial in our senior years, there is a very different stage of life when collagen protein intake is equally if not even more important. That time is during fetal development.[i] Even if you are well past your child-bearing years, please read on as you may be able to share this helpful information with expectant parents.

Many women who I help come in with hormonal problems, infertility, or pregnancy complicated by obesity or poor blood sugar control. The women I don’t see anywhere near as often are those that do not experience problems conceiving or carrying a baby to term. This is a real shame because all women can benefit from a thorough review of their diet by a knowledgeable dietitian or nutritionist, before, during, and after pregnancy. Whether pregnant or trying to conceive, my patients consistently tell me how valuable the information I shared with them was and how glad they were to have met with me. In the words of one mother-to-be, “I didn’t know what I didn’t know.”

Unfortunately, many women continue to have gaps in their prenatal nutrition despite following the recommended dietary guidelines and receiving the best obstetrical care. Could these gaps lead to problems for a woman or her baby? Based on the growing body of research in reproductive nutrition, the potential is there.[1]

My goal is to see all women be fully nourished during the critical life stages of pregnancy and lactation. In my practice, one of the most frequent recommendations I make to pregnant patients is that they consume more collagen protein. They are surprised to learn that daily servings of skin-on organic chicken, gelatin dishes, and soups made with bone broth are important parts of their prenatal diet. And I have yet to meet with an expectant mother that was already in the habit of eating these nourishing foods prior to our first appointment.

One of the main reasons collagen protein appears to be essential during pregnancy is, once again, that little amino acid glycine. According to nutritional scientists, “the shortage of glycine may become serious in conditions such as pregnancy.” [ii] What might “serious” mean for a pregnant woman and her baby? Pregnancy creates a higher demand for glycine due to the increased collagen and elastin synthesis taking place in the expanding uterus and stretching skin. As a result, glycine may become a limiting factor for protein synthesis in the developing fetus. Without enough available glycine, there is the possibility that fetal growth will be restricted, albeit to an unknown extent. Additionally, in studies on pregnant rats, glycine supplementation reversed the high blood pressure and the blood vessel dysfunction that occurred when they were fed lower protein diets.[iii] These findings point to an important (pivotal per authors) role for dietary glycine in the adaptations required during pregnancy to support healthy maternal circulation.

Recall from chapter 3 that some scientists consider glycine to be one of the conditionally-essential amino acids because the human body cannot synthesize enough glycine to meet more than its most basic survival needs. There are numerous health benefits to consuming sufficient quantities of glycine through diet, 10 grams per day appears to be about optimal.[iv] And while 10 grams may be sufficient for almost every healthy adult, it is almost certain that a moderately higher amount would be beneficial during pregnancy, especially during the last two trimesters when the most rapid growth occurs.

To better understand the role of glycine, we need to look at it in the context of the overall diet. It is generally recommended that a woman consume an additional 25 grams of protein per day during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, or a total of 71 grams protein per day. A lot more protein is not advisable. High protein diets that exceed 20% of calories from protein can impair fetal growth, according to a 2013 review of the research.[v] [2] And an excess of the amino acid methionine relative to glycine is not optimal either. Too much methionine not only increases the need for glycine but may lead to other undesirable effects on the child’s long-term physiology.[vi]

Where would an excess of methionine come from? From high protein diets that are often thought of as healthy, and especially ones with predominantly lean muscle protein, like chicken breast and lean meat. So whether it is the total amount of protein or methionine, or the ratio of methionine to glycine consumed, it is important to make sure that the sources of protein are balanced, avoiding too little as well as too much. Nutritionists often referred to this as the “Goldilocks Principle” and it can be applied to almost any nutrient, supplement, or food that we consume.

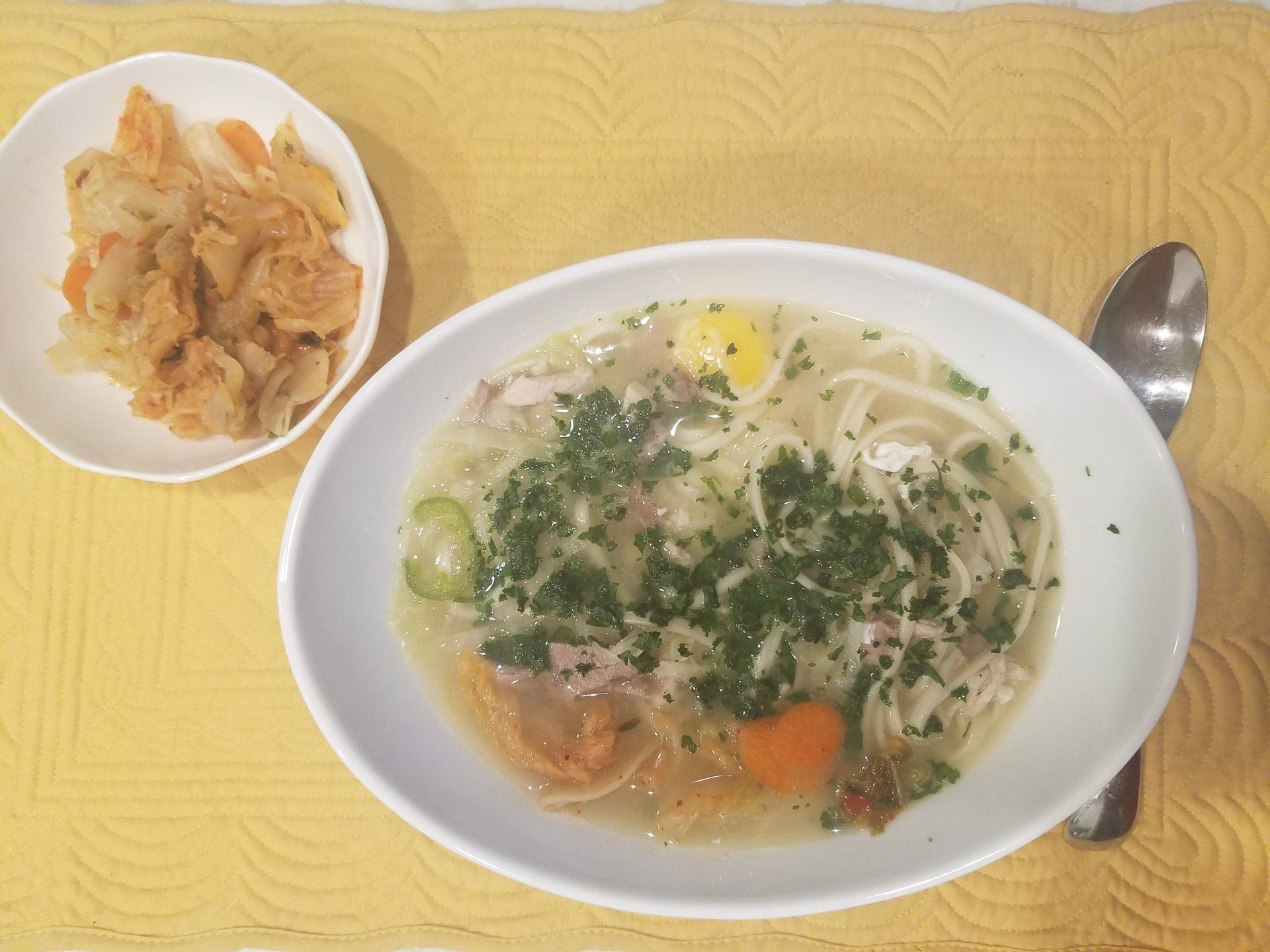

Of course collagen protein, although an excellent source of glycine and other amino acids, is just one component of a nourishing diet! When I am asked what the perfect meal for a pregnant woman is, I answer: a great homemade soup made with collagen-rich bone broth, one to two ounces of meat, poultry, organ meat, or safe seafood, one ounce of soft-cooked tendons such as in the traditional Vietnamese dish Pho, plenty of fresh leafy greens, a small potato or sweet potato, a half-cup of a favorite type of legume, a whole egg or even better two egg yolks, a bit of seaweed rich in iodine, and a handful of cilantro or other green herbs. On the side would be a fermented vegetable like sauerkraut. This would be accompanied by a good source of calcium such as a grass-fed cheese or yogurt, along with a fresh fruit for dessert, topped off by a little sunshine for vitamin D!

Come to think of it, this is a perfect meal for just about anybody, at any time!

Recovery after delivery.

Collagen protein consumed throughout pregnancy could have further benefits after delivery. We already know that pregnant women need more collagen protein because a high proportion of them have been shown to have a glycine insufficiency.[vii] It has also been shown that with each pregnancy, the collagen and elastin content of a women’s uterus increases.[viii] Stretch marks happen when a women’s belly expands faster than her skin can keep up with, causing the collagen and elastin fibers in your skin to break. Because collagen protein has been shown to increase the elasticity of the skin, it just might minimize the appearance of those annoying stretch marks. Other than not gaining excessive weight during pregnancy, medical experts don’t know how to prevent stretch marks. Collagen protein in the context of a nourishing diet could be your best defense.

[1] Maternal undernutrition may be more prevalent in developed countries than the medical community recognizes. Insufficient intakes of vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin K2, vitamin B6, biotin, choline, zinc, iron, iodine, glycine, and/or omega-3 fats are not uncommon. While outright birth defects may not result, a shortage of one or more of these nutrients could adversely impact a child, potentially contributing to physical or mental health challenges at birth and over his or her lifetime. This is still a controversial theory, but as the research expands on the “Developmental Origins of Disease” in the field of epigenetics (how the environment impacts our genes), I believe we will continue to see relationships between undernutrition and disease revealed. From Masterjohn C: Vitamins for Fetal Development

[2] For the typical 5 foot 5 inch, 150 pound female, 20% of calories equates to 100 grams of protein when consuming 2000 calories in the first trimester, and 120 grams of protein when consuming 2400 calories in the third trimester.

[i] Melendez-Hevia E, et al. A weak link in metabolism: the metabolic capacity for glycine biosynthesis does not satisfy the need for collagen synthesis. J Biosci. 2009; 34:853-872.

[ii] Melendez-Hevia et al. A weak link in metabolism:…..

[iii] Brawley L et al. Glycine rectifies vascular dysfunction induced by dietary protein imbalance during pregnancy. J Physiol. 2003;554:497-504.

[iv] Melendez-Hevia E, De Paz-Lugo P, Cornish-Bowden A, Cardenas ML. A weak link in metabolism: the metabolic capacity for glycine biosynthesis does not satisfy the need for collagen synthesis. J Biosci. 200934(6):853-872.

[v] Liberato SC et al. Effects of protein energy supplementation during pregnancy on fetal growth: a review of the literature focusing on contextual factors. Food Nutr Res. 2013;57(1).

[vi] Rees WD, Wilson FA, Maloney CA. Sulfur amino acid metabolism in pregnancy: the impact of methionine in the maternal diet. J Nutr. 2006;136(6 Suppl):1701S-1705S.

[vii] Lewis RM et al. Low serine hydroxymethlytransferase activity in the human placenta has important implications for glycine supply. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1594-1598.

[viii] Woessner JF, Brewer TH. Formation and breakdown of collagen and elastin in the human uterus during pregnancy and post-partum involution. Biochem J. 1963;89:75-89.